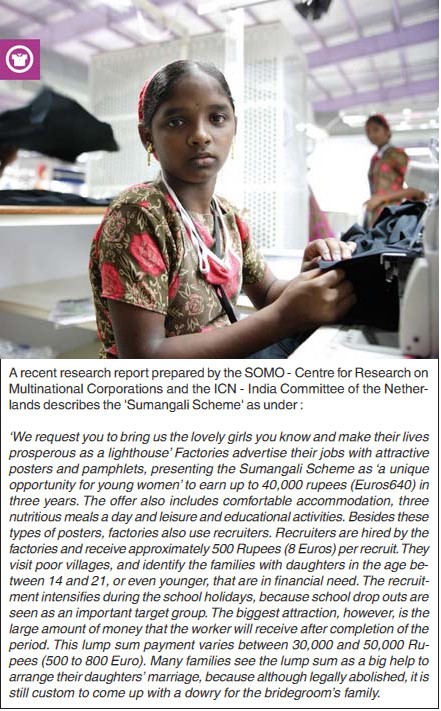

Over the past decade, the garment industry in Tamil Nadu has experienced major growth. Thousands of small and medium sized factories are involved in the complex process of turning cotton into clothing. The Tamil Nadu garment industry is largely export-oriented. Customers include major European and US clothing brands and retailers. These companies source directly from smaller textile and garment factories as well as from larger enterprises.

American perception about an employment scheme – called Sumangali – for girls in the Tamil Nadu’s textile industry is the fresh cause for worry for the $11-billion Indian garment export industry. International retailers from the US and Europe like GAP, Walmart, C&A, H&M, Primark, Mothercare and Tesco have already asked their suppliers from the region to scrap the Sumangali scheme that purportedly encourges bonded labour (read their response here).

Indian apparel industry earns 80% of its business from Europe and the US, but has been blacklisted by the US Department of Labour for engaging child labour and forced labour. According to the report prepared by the U.S. Department of Labor, the hosiery and knitwear units of Tirupur area employ about 50,000 girls mostly in the age group between 14 and 18 years under the ‘Sumangali’ scheme. About 10% girls are even younger than 14 years. According to this report : “The girls employed under the scheme are exploited. They are not allowed to go home as staying in the hostels in the factory premises is mandatory. Cost of food and hostel rent are deducted from their small monthly payments. They are allowed to (taken to) go to market once in a fortnight but are accompanied by guards and have to return in a small time of an hour or so. Sexual exploitation of girls is rampant. Doctors in the area are witness to large number of teenage termination of pregnancies of these girls. They are made to work hard and had to work in standing position, which creates health problems”.

Close to 120 mills part of the Southern India Mills Association currenlty employ women under what it now calls “apprentice scheme with hostel facility”. K Selvaraju, SIMA secretary general insists that the term “Sumangali” has been done away with. “Nevertheless, it is misleading to label the scheme as bonded labour. German-firm TUV Rheinland even audits our mills to certify women employment standards,” he clarified.

The industry insists that it has been offering dignity of labour to the otherwise illeterate and poor women through employment. The idea to pay came from parents who sought that the money be kept with the employers as saving, says S.V. Arumugam, chairman of apex industry body Confederation of Indian Textile Industry. Armugam who is the director of Shiva Textiles adds that the socio-cultural problem of the region can not be explained to NGOs who perceive this as human rights violation. “You can not permit the women employees leave the dormitories at 1 am just because the western world perceives this as violation of human rights,” says the man who has 400 women under this scheme. “But we have discontinued payment of lumpsome and encourgae their parents to collect salaries every month so that no one points fingers at us,” he says.

The Indian knitwear hub in Tirupur, 400 kms from TN capital Chennai, meanwhile, has pressed the panic button.

Getting Rs 12,500 crore business from European and US buyers, the exporters are in no mood to lose clients. Tirupur sources yarn from Coimbatore and insists that its supply chain is free of Sumangali scheme. After facing allegations of child labour in 2008, the knitwear hub does not seek to associate with anything that could jeopardise business.

“Although we know it is not slavery, 27 of our clients including big buyers like Gap, Primark, Walmart, H&M, C&A and Tesco have asked us to discourage the Sumangali scheme in the supply chain. We have already asked SIMA and the Tamilnadu Spinning Mills Association to abolish the scheme and encourge fair employment practices,” Tirpur Exporters Association is reported to have told. In September 2011, the Tirupur stakeholders’ forum comprising TEA, labour unions, NGOs and Brand Ethics Working Group came out with a framework for TEA members on women employment, categorically decrying Sumangali scheme.

Social Awareness and Voluntary Education (SAVE), a local NGO in Tirupur, that has been crying hoarse over this scheme asserts it is a form of bonded labour. “Girls are kept captive in hostels, not allowed to make phone calls and their salaries are withheld for three years. They are paid poorly – Rs 40- Rs 60 a day against Rs 184 which is the minimum wage. They are made to work for 12 hours. In some cases, contracts have been illegally terminated and girls have left empty-handed. This scheme has to go. Employers must pay regularly and respect freedom of movement,” said A. Aloysius, Director, SAVE.

Stakeholders however, assert that similar pre-marriage schemes prevail in China, Bangladesh, Vietnam, Indonesia and Thailand. “The scheme is extremely popular with the workers, but equally unpopular with trade union leaders because they do not get their pound of flesh from the workers. NGOs on the other hand, are unable to find enough people for conversion and hence, they give bad name to the industry,” a senior industry observer is reported to have observed.

However, AEPC believes that while all the negative aspects of Sumangali have been reported, positives have been missed out. “While a visit to mills implementing this scheme looks satisfactory, in absence of documentation of salaries, it is difficult to ascertain if the wages are at par with minimum wages or low. Secondly, allegations of girls been thrown out without salaries before completion of three years are worrisome,” says AEPC.

SOMO and ICN have urged brands and retailers to adhere to international labor standards and local labor laws and accept a broad definition of supply chain responsibility. To end the Sumangali Scheme, they have suggested to set up genuine and credible grievance mechanisms at the supplier level. They have urged all companies and local and international civil society organisations involved to work together instead of changing suppliers.