Shuji Uchikawa

Director-General Research Promotion Department

Institute of Developing Economies, Japan External Trade Organization (IDE-JETRO)

Summary

This paper tries to compare knitwear clusters in Ludhiana and Tiruppur. While Ludhiana is producing woolen knitting wear mainly for domestic market, Tiruppur concentrate on cotton knitting wear mainly for export market. There are four similarities between the two clusters. First, vertical networking among units specializing in different parts of the production process is working effectively. Second, information on market is shared among producers through intermediaries such as wholesalers, retailers and other marketing agents. Third, both clusters depend on migrant workers. Fourth, apparel industry contributes to improvement of household income in neighbouring villages. On the other hand, there is difference in the two points. First, while Ludhiana is catering mainly for the domestic market, Tiruppur is export-oriented cluster. Second, communities of owners are different in the two clusters.

Introduction

India has maintained stable economic growth since 1981. Although manufacturing sector has developed, supplying mainly for expanding domestic market, employment in the sector has not increased dramatically. The National Manufacturing Policy announced by commerce minister in 2011 put two objectives. The share of manufacturing in GDP will be raised up to 25 percent by 2022. Further 100 million employments will be created by 2022. Both are challenging. The policy pays special attention to small and medium enterprises (SMEs). SMEs are estimated to employ about 59 million persons in 26 million units throughout the country. It recognized that “global experience of manufacturing has shown the advantages of clustering and agglomeration as it enhances supply chain responsiveness, provides easier access to market talent and substantially lowers logistic costs”. Industrial cluster of SMEs may be a key to accomplish the two objects.

This paper tries to compare knitwear clusters in Ludhiana and Tiruppur. While

Ludhiana is producing woolen knitting wear mainly for domestic market, Tirupur concentrate on cotton knitting wear mainly for export market. SMEs have developed rapidly in both clusters. The first section examines the development of apparel industry in India. The second section analyzes change of the world market. The third section investigates conditions of two clusters. The fourth section finds the similarities and differences between the two clusters to make clear the characters of Indian apparel industry.

The Development of Apparel Industry in India

Average GDP growth rate between 1993-94 and 2009-10 was 6.9 percent. While the share of the tertiary industry in GDP rose from 46.6 per cent to 65.2 per cent during the period, the share of manufacturing did not change (Table 1). Service industries contributed to the rapid economic growth. While the share of agriculture in total employment declined from 66 to 53 percent during the period, the share of manufacturing did not change (Table 2). Although employment in the manufacturing sector increased, it could not absorb surplus labour in the rural area.

Apparel industry has depended on seasonal cheap labour force in India. Skill and long experience are not required much in the industry. It is useful to examine how the apparel industry has developed in order to explore the potential to absorb surplus labour in rural area. In India, as apparel goods had been reserved for small scale industries (SSIs), the large manufacturers could not produce them. Under import-substitution industrialization strategy, two roles: expansion of employment opportunities and production of consumer goods were provided to SSIs. SSIs are defined by the investment in fixed assets in machinery, whether held on ownership term or on lease or hire purchase. The investment limit has been varied by the government from time to time. The firm above the capital ceiling could produce apparel only when they committed to export more than 75 per cent of its output. Reservation refrained graduation from a small scale unit to medium and large scale unit. Readymade garments except knit products and knit products were dereserved in 1997 and 2005 respectively. Besides, it is argued that job security regulation discourages small units to grow to large. Industrial dispute Act prohibits lay-off, retrenchment and closure by industrial units employing not less than 100 workers without prior permission of the government. In some cases, an owner has multiple units specializing on various processes and controls all process as a company. Many small apparel firms are not registered to avoid tax payment. Although registration of a small scale unit is not compulsory, registered units are eligible for availing different types of government assistance such as medium and long term loans from banks, credit guarantee scheme. But they are afraid of being captured by governments. Therefore, many apparel units are dropped from industrial statistics like Annual Survey of Industries and National Sample Survey. As a result, SSIs are built in the structure of apparel industry. Even after readymade garment and knit products were dereserved, SSI is still main players in the apparel industry.

The relationship between export and domestic market is examined historically. In the 1970s, exports of apparel increased rapidly. Subcontracting developed rapidly in the 1970s in the apparel industry, and many small contracting units were set up. These units employ semi-industrial workers who come down to the cities during slack agricultural period and return to their villages for sowing, harvesting and festival seasons. Such a labour force makes feasible subcontracting, as the production units can use low wage labour during the season when export garments are produced (Kumar 1988). In 1985 most exporters concentrated on exports and did not supply the domestic market. A sample study conducted by the Trade Development Authority in 1985 contained profiles of 194 leading manufacturers and exporters. Exporters of these firms take together accounted for 51.8 per cent of India’s export of apparel in 1983-84. Among the 194 firms, 124 were totally export-oriented units (TDA 1986).

In the 1980s, readymade garment started to spread in the domestic market due to a change in fashion from traditional dress to western. Moreover, brand names began to command wide acceptance (Uchikawa 1999). Estimated aggregated domestic consumption of readymade garment and hosiery increased rapidly from Rs 12.3 billion in 1981 to Rs 86.4 billion in 1992. On the other hand, exports of readymade garment and hosiery rose from Rs 6.5 billion to Rs 79.6 billion. Although exports grew faster than domestic market, domestic market was larger than export even in 1992. The domestic market is more easily manageable commercially since the demand is not as unstable as in the export market. The risk of obsolescence, rejects, surplus, and heavy inventories are minimized in the domestic market (Kantilal 1990). Some large exporters started production for domestic market in the 1980s.

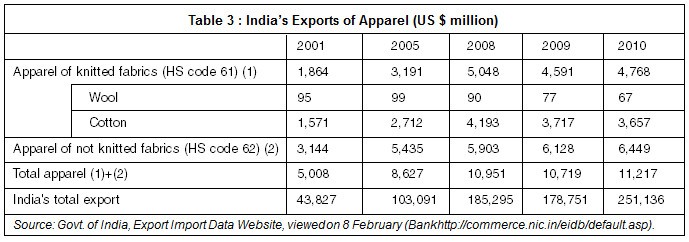

Exports of apparel increased in the 1990s. In the first half of 1990s, India’s

apparel exports concentrated on women’s outwear of not knitted fabrics and men’s shirts of not knitted fabrics. These two items accounted for more than 50 percent (Ramaswamy and Gereffi 2000). T-shirts rose as a main export item in the 2000s. In 2010, T-shirts, blouse and dress and men’s shirts accounted for 48.5 per cent. Table 3 shows that exports of apparel of knitted fabrics came up rapidly. But they decreased due to shrinkage of demand in developed countries after 2008. Apparel of knitted and not knitted fabrics is exported mainly for EU and North America markets. Between 2007-08 and 2010-11 the market share of EU and North America was around 80 per cent and 75 per cent in apparel of knitted fabrics and apparel of not knitted fabrics respectively.

While exporters are facing severe competition with cheap products from other developing countries such as China, Bangladesh etc, domestic market is growing. In 2008, outlet in domestic market and export was US $ 30 million and US $ 10 million (AEPC 2009).

In this period, India’s apparel industry had competitiveness at the three points (Uchikawa 1998). First, cheap seasonal worker is easily available. Second, it has easy access to a great variety of fabrics. The Indian textile industry consists of the handloom, powerloom, and mill sector, producing cotton, blended and man-made fibre material. Moreover, import of cheap raw material became easy in the 2000s. Third, subcontracting has developed in clusters of apparel industry.

Change of Apparel World Market

In automobile and electric industries, producers play an important role in development of new products. On the other hand, large retailers, brand-name marketers, and trading companies are making decision on design and marketing strategy. The former depend on a producer-driven commodity chains, the latter on a buyer-driven commodity chains. Physical production activity separates from the design and marketing stages. Large retailers, brand-name marketers in developed countries have set up decentralized production net work in developing countries. During the 1960s and 1970s, East Asian NIEs like Korea and Hong Kong increased exports of apparel. These economies moved from assembly i.e. cut, make and trim to original equipment manufacturing (OEM). In the OEM, the supplying firms procure material by themselves and make products according to the design specified by the buyers. The product is sold under the buyer’s brand name.

During the 1980s, wages in the East Asian NIEs rose, manufacturers in the economies shifted some or all of the requested production to affiliated offshore factories in developing countries like China and Bangladesh. Foreign Direct Investment into China from Korea increased (Ramaswamy and Gereffi 2000). Indigenous large firms rose in China, absorbing knowledge from foreign factories.

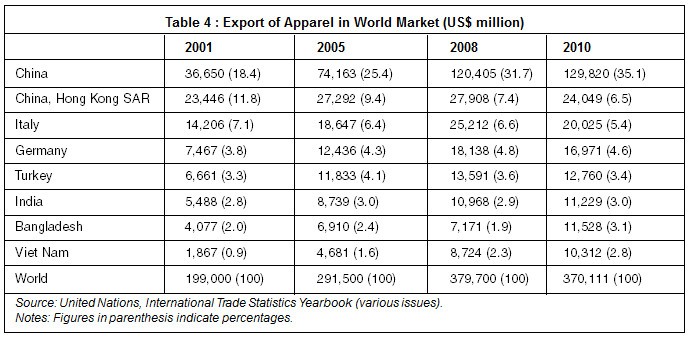

The Uruguay Round of multilateral trade negotiations came to the Agreement on Textiles and Clothing. It decided to phase out quota restriction on imports from developing countries by developed countries on the basis of Multi-fibre Agreement (MFA) over a ten-year period. The agreement called for integration of 16 per cent of imports in 1990 into GATT in 1995, 17 per cent in 1998, and 18 per cent in 2002, with remaining 49 per cent to be integrated at the end of the phase-out period, in 2005. It was expected that China would expand her share in the market of USA and EU. Even after the MFA was abolished, EU and USA had imposed import regulation on textiles products from China. It was withdrew it in 2008. Table 4 shows China’s share rose rapidly in spite of import regulation. After it was withdrawn in 2008, the share expanded further. In 2010 China and Hong Kong accounted for more than 40 per cent exports in the world market. India has maintained its share. On the other hand, Bangladesh and Viet Nam are increasing exports, inviting FDI. As FDI into India has been less due to less incentive for foreign investors, Indian apparel firms have less opportunity to get knowledge from foreign factories.

Comparison of the Two Clusters

Industrial clusters consisting of SSIs have developed in developing countries. Cluster is defined as sectoral and spatial concentrations of firms. Schmitz and Nadvi (1999) abstracted collective efficiency as common factors for cluster development from case studies. It is competitive advantage derived from external economies and joint action. They emphasized active factors from firms in the clusters which diversified performance of cluster development. This paper focuses on Ludhiana and Tiruppur. There are a lot of literature to analyze development of Ludhiana and Tiruppur.

Ludhiana :

Ludhiana has developed as the hub of woolen knitwear industry. Ludhiana’s knitwear cluster is diversified and has created backward linkage. Some woolen knitwear factories accumulated capital and diversified into wool spinning. Later cotton and acrylic spinning mills, dyeing subcontractors, and textile machinery manufacturers were set up.

Asian Clothings of Tirupur is a global apparel and knitted garments manufacturing company producing the Brands like KAPPA, SIMPSON, NBA, SERGIO TACCINI, ACMILAN, ONYX, INTER, A-STYLE, MENS UNDERWEAR, SMILE and JUVENDUS. The Company exports its products to global markets such as usa, Austria, Belgium, Slovenia, Italy and France. The company is a leading integrated knitwear production house. The Dyeing section is shown in this picture.

The long-term government contract between Indian and Soviet Union encouraged woolen knitwear firms to export to Soviet Union. Large quantity of low quality and cheap items were sold to the market. Ludhiana’s knitwear producers exported over half their total production. In the domestic market, brands were established in the upper-end market. Even middle segment of the domestic market began to develop a demand for new design and better quality during the 1980s. Some large and medium-sized producers exported the low-quality items to a stable and high-volume assured market and supplied high-quality items for a competitive domestic market. They ran virtually two distinct systems of work organization. In a typical case, manual handflats were used for export market and a wider range of machines including handflats, powerflats and circular knitting machines for domestic market to accommodate a greater range of fine yarn. While workers owned handflats, depending on traditional manufactory work and ownership system, firms owned all the equipment on the domestic side. As a result, the knowledge to operate production in different market conditions was accumulated.

The collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991 forced them to find new outlets. But Ludhiana cluster could recover quickly, shifting direction to more demanding European and North American markets. Tewari (1999) argued three reasons of quick recovery. First, the experience to supply branded items to the domestic market was useful to move quickly from the Soviet Union market to new market in EU and USA. The interaction between the export and domestic market created the ability to cope with high-quality export market in the 1990s. Second, much attention was paid to making non-equipment related changes to the production process. Third, intermediaries worked effectively as the channel of market access, transfer of knowledge and monitoring for local producers. Foreign buyers utilized existing local distribution channels to offer small-scale contracts.

Apparel industry in Ludhiana diversified its products to jackets for winter. As domestic market for woolen knitwear and jackets for winter grew rapidly in the mid-2000s, main outlet shifted from export to domestic market. The Apparel Export Promotion Council (AEPC) report describes present conditions of Ludhiana knitwear industry (AEPC 2009). Ludhiana almost monopolizes winter wear production for the country. Around 95 per cent of India’s woolen and acrylic knitwear products are produced in Ludhiana. There are approximately 10,000 to 12,000 units including spinning, weaving, knitting, chemical processing and garment units. 2,500 units are manufacturing apparel for both export and domestic markets. Among them, 100 units are large size with more than 125 sewing machines, 700 units medium size with 40 to 125 sewing machines, 1,700 units small size with less than 40 sewing machines. In addition to apparel producers, 6,000 units are receiving job work such as knitting, stitching, embroidery, and patch work. 200 units are processing fabrics. At present, there are very few export oriented units.

Because the share of exports in total turnover in Ludhiana is only 20 per cent, domestic market is more important than export. The direct and indirect employment in the apparel industry in Ludhiana is approximately 350,000 to 400,000 persons. Direct employment is less because the majority prefers to outsource most of their work to the local subcontractors. Producers want to employ workers on contract basis to avoid payment of provident fund and the employees state insurance fund to their employees.

Interview with managers of nine companies in Ludhiana was hold in 2010 and 2011. Eight companies among nine are members of Knitwear and Apparel Manufacturers Association of Ludhiana. The members are supplying winter cloth with their own brand mainly for domestic market. Because design is changed every year, their production period is from March to November. They employ seasonal workers, who come from Bihar and Uttar Pradesh etc. and go back to their villages after production period. Many workers rejoin the same factory due to easiness of adjustment. But some workers shift from a factory to another factory for higher wages. In the eight firms, 12-hour (one and half shift) six day a week is the norm. Workers, who are paid on piece rate basis, want to work for longer hours to earn more money. Jacket producers import synthetic fabrics from China and operate cutting, stitching and packing in their house. They outsource other process to subcontractors. Woolen knitwear producers concentrate on knitting and outsource embroidery work. These final producers utilize network of SSIs specializing in various stages of process. On the other hand, a100 per cent exporting unit get contract of OEM production and growing very fast. The unit is located in suburb area due to low land prices. The foreign buyer impose social audit on the unit, it must limit working hours within 8 hours excluding break. Its workshop is maintained well and clean. Not only computer-controlled knitting machine but also handlooms are operated to produce various fabrics, which foreign buyer specify. It is outsourcing labour intensive process to households in neighbor villages.

Collective efficiency is functioning well in Ludhiana. It includes not only backward linkage but also spillover of knowledge. The cluster shared the knowledge on inputs, production method, and market among producers. They have access to a common labor pool, common input source, and common distributional network. Wholesalers, retailers and other marketing agents who have daily contact with market are main channels of feedback for producers about changing demand. Ludhiana has changed its main outlet from export to Soviet Union to export to USA and EU, further to the domestic market.

Tiruppur :

Tiruppur locates in the middle of cotton belt and has a large exchange market of raw cotton. Many spinning mills are operating in Coimbatore. The early 1970s Tiruppur catered only for the domestic market. Verona, a garment importer from Italy came to Tirupur in 1978 to buy white T-shirts. It was the turning point of Tiruppur. Export of cotton knitwear from Tiruppur grew rapidly. As size of cotton knitwear firms in Tiruppur is smaller than that in other countries like China and Bangladesh, they find their way into competing in low-volume segments with grater fashion contents.

Tiruppur locates in the middle of cotton belt and has a large exchange market of raw cotton. Many spinning mills are operating in Coimbatore. The early 1970s Tiruppur catered only for the domestic market. Verona, a garment importer from Italy came to Tirupur in 1978 to buy white T-shirts. It was the turning point of Tiruppur. Export of cotton knitwear from Tiruppur grew rapidly. As size of cotton knitwear firms in Tiruppur is smaller than that in other countries like China and Bangladesh, they find their way into competing in low-volume segments with grater fashion contents.

Tiruppur specializes in the low volume mid-fashion segment, particularly in children’s and women’s wear and supplies to some of the world’s leading retailers like Marks and Spencers. Over the last decade, international buyers have shortened the lead time for export to reduce costs of maintain inventories. The lead time of exporters was reduced from three to four months to about a month and a half to two months (Vijayabaskar 2011). Apparel producers in Tiruppur could adjust the changing situation. It emerged as the largest exporter of cotton knitwear from the country. Nominal export amount jumped from Rs 97 million in1984, Rs 99, 500 million in 2007-08. Export accounted for 74 per cent of total turnover in 2007-08 (Tiruppur District 2012). About 80 per cent of India’s total cotton knitwear exporters are from Tripur.

Firms are highly segmented in terms of markets, the types of garment produced for different markets, and there is a huge range in the quality of cloth. The very small firms are using a very coarse knitted fabric. Small cutting firms cooperate horizontally with other very small making up firms. They cannot enter exports due to low quality.

On the other hand, the firms with contracts from foreign agents must comply with the conditions of production such as design, type of fabric, dyeing and finishing. The larger firms transact with other firms which already have the capacity and skills to make the more sophisticated garments. Only the middle-size has possibility of improving knowledge of particular designs and gaining experience of better quality fabrics through subcontracting from large firms which are supplying to foreign branded distributers (Cawthorne 1995).

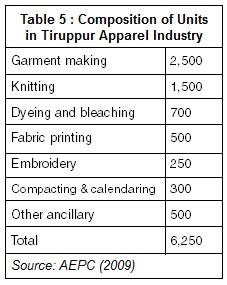

The AEPC report describes present conditions of Tiruppur knitwear industry. Approximately 6,250 units are operating in Tiruppur apparel industry. Table 5 shows process-wise composition. Among 2,500 garment making units, 500 are large size with more than 500 sewing machines and exclusively exporting. There are 60 to 70 export oriented integrated units, engaged in all kind of activities commencing from knitting to garmenting barring one or two operations in the value chain which are outsourced. 500 units are medium size with 40 to 100 sewing machines and supplying to export or domestic markets. 1,500 units are small size with less than 40 sewing machines and supplying to domestic market or receiving subcontracting from medium and large size units. The direct and indirect employment in the apparel industry in Tiruppur is approximately 350,000 to 250,000 persons. The share of domestic market is rising.

While margin against export is shrinking due to increased competitive pressure, domestic demand is expanding. Big players in the domestic market have started sourcing their requirements from Tiruppur which include mainly T-shirts of all types and undergarments. The share of export in total turnover decreased from 78.6 per cent in 2006-07 to 74.0 per cent in 2007-08.

The specialization in cotton knitwear implies seasonality of production. The

fluctuation of demand and effects of reservation policy enhanced the need to rely on inter-firm networking and undermines the incentives for vertical integration. Demand for labour also fluctuates on production volume. Rapid increase of export has led to a substantial surge in demand for seasonal workers. Even relatively large firms often rely on contractors for bulk of their labour requirement. During the peak season of production, some worker shift to other firms for higher wages. High inter-firm mobility of labour discourages firms to offer in-plant training (Vijayabaskar and Jeyaranjan 2011). Vijayabaskar (2011) points out three main sources of workers. First, agricultural workers and workers engaged in other informal activities in the neighbouring villages join the industry. Workers commute by buses and trains from various villages surrounding Tiruppur at a radius of nearly 50 km. Large export firms moved to set up factories in these villages. Second, migrants come from their village with their families and settle down in Tiruppur. Third, migrants alternate between rural and urban workspaces.

Agrarian Gounder caste rose as owner of knitwear firms in the 1990s. Chari (2000) pointed out that Gounder ex-workers accounted for 42 per cent owners of the South India Hosiery Manufacturers Association (domestic association) and 27 per cent exporters of Tiruppur Exporters’ Association. Moreover, many owners are the second generation of Gounder ex-workers. This suggested that workers with peasant background became owners of knitwear firms in Tiruppur. Many owners who began as workers were receiving support from the same community in both material and nonmaterial form. Nonmaterial support includes sustained subcontracting order, recommendation for working capital loans necessary for business through networks. Support among the same community is crucial for their rapid rise. Upstart Gounders entered knitwear business and set up SSIs. Consequently, the share of small firms increased in Tiruppur.

The knitwear industry in Tiruppur stands on cross road. Water pollution

became serious because dying and bleaching units were not following the pollution control norms. Finally the High Court ordered the closure of all the 720 dyeing and bleaching units on 28 January 2011. Only a few large firms could set up the equipment to treat polluted water.

The Similarities and Difference between the Two Clusters

From above analysis, we can extract four similarities between the two clusters. First, vertical networking among units specializing in different parts of the production process is working effectively. All units are getting benefits from the system of division of labour. As subcontracting makes apparel producers to concentrate investment in specific important process like knitting and cutting, it minimizes the need of vertical integration within the firm. As availability of existing network limit initial investment amount, entry to the apparel industry is easy in both clusters. Cawthorne (1995) defines outcontracting and incontracting. Outcontracting takes place between firms specializing in different processes. Incontracting has developed within some of the larger firms where an owner employs production manager who is responsible for employing labour for a particular production process in each unit. Both clusters compensate disadvantage of smaller size with such efficient and flexible networking. Although knitwear exporters cannot compete with China in the standard items appropriate for mass production, they have international competitiveness in the low volume mid-fashion segment.

Second, information on market is shared among producers through intermediaries such as wholesalers, retailers and other marketing agents. The information on design and fashion brought by them has conducted knitwear producers to right way. Information is transferred through daily interaction. Small firms are observing what large firms are doing.

Third, both clusters depend on migrant workers. Producers can adjust labour

force to peak season of production. Migrant workers want to work for longer hours to remit more money to their household. Keshri and Bhagat (2012) analyzed the relationship between poverty and migration, utilizing unit level data from the 64th round of the National Sample Survey (NSS) conducted in 2010. Monthly per capita consumer expenditure (MPCE) was used as a measurement of poverty.

They classified temporally the number of migrant per 1,000 persons according to MPCE quintiles. In the NSS, the period of temporally migration is defined is that of 30 days to six months. The migration rates in the lowest and the second lowest MPCE quintile in the rural area was 44.8 and 32.1 respectively. The lower is MPCE quintile, the higher is migration rates. It can be concluded that most of seasonal workers are coming from low income household in the rural area.

Fourth, apparel industry contributes to improvement of household income in

neighbouring villages. As new large factories are set up in suburb area in order to get land at lower price and low cheap labour force, commutable area expanded to the area which were slightly far from industrial area in the cities. Outsourcing area from apparel firms to household also expand. More household can access the employment opportunities.

On the other hand, there is difference in the two points. First, while Ludhiana is catering mainly for the domestic market, Tiruppur is export-oriented cluster. The interaction between the export and domestic market contributed to market diversification and upgrade of products in Ludhiana. The same phenomena have not occurred in Tiruppur. Why large firms in Tiruppur do not create their own brand names for the domestic market must be examined.

Second, communities of owners are different in the two clusters. The knitwear industry in Ludhiana is dominated by Punjab’s trading communities like Jains and Banias. Our survey found some ex-worker owners in Ludhiana but no agrarian community are involved in the knitwear industry. On the other hand, agrarian Gounder caste rose as owner of knitwear firms in the 1990s. At present, Gounder is majority of industrial association members. Owner in the community depend on each other, getting support material and nonmaterial form.

Conclusion

The growth of knitwear industry has created employment opportunity for households in neighbouring villages and temporary migrant workers. If the industry develop further, more surplus labour force in rural might be absorbed. On the other hand, labour shortage becomes more serious. Inflow of migrant workers cannot catch up increase of demand for labour force. Besides, employment availability in the rural area might increase because of rural development and rural development employment scheme. If firms want to employ more workers, they must raise wage and diversify their products to high value added items. Ludhiana and Tiruppur concentrate on the low volume mid-fashion segment, depending on seasonal cheap labour force. Rise of real wages may affect competitiveness of knitwear industry in both clusters. Although the industrial structure on the basis of networking of small factories contributed to the development of the clusters, it restricts diversification of their products.

Reference :

- Apparel Export Promotion Council (2009), Indian Apparel Clusters: An Assessment, Gurgaon, Apparel Export Promotion Council.

- Cawthorne, Pamela M (1995), “Of Networks and Markets: The Rise and Rise of a South Indian Town, the Example of Tiruppur’s Cotton Knitwear Industry”, World Development, Vol. 23, No.1.

- Chari, Sharad (2000), “The Agrarian Origins of the Knitwear industrial Cluster in Tiruppur, India”, World Development, Vol. 28, No.3.

- Kantilal, Ila (1990), The Apparel Industry in India, Ahmedabad, National Information Centre for Textile and Allied Subject.

- Keshri, Kunal and R B Bhagat (2012), “Temporary and Seasonsl Migration: Reginal Pattern, Characteristics and Associated Factors”, Economic and Political Weekly, Vol. 47, No.4.

- Kumar, Anjali (1988), India’s Manufactured Exports, 1957-80: Studies in the Development of Non-traditional Industries, Delhi, Oxford University Press.

- NSSO (National Sample Survey Organization)(1997), Employment and Unemployment in India 1993-94, Delhi, NSSO.

- NSSO (2011), Key Indicators of Employment and Unemployment in India 2009-10, Delhi, NSSO.

- Ramaswamy, K. V. and Gary Gereffi (2000), “India’s Apparel Exports: The Challenge of Global Markets”, The Developing Economies, Vol. 38, No. 2, pp. 186-210.

- Schmitz, Hubert and Khalid Nadvi (1999), “Clustering and Industrialization: Introduction”, World Development, Vol. 27, No. 9, pp 1503-14.

- Tewari, Meenu (1999), “Successful Adjustment in Indian Industry: the Case of Ludhiana’s Woolen Knitwear Cluster”, World Development Vol. 27, No. 9, pp.1651-71.

- Tirupur District (2012), Tirupur District Official Website, viewed on Feb 1 (http://tiruppur.nic.in/textile.html).

- Trade Development Authority (1986), Supply Study on Readymade Garments, Delhi, Trade Development Authority.

- Uchikawa, Shuji (1999) “Economic Reforms and Foreign Trade Policies: Case Study of Apparel and Machine Tool Industry”, Economic and Political Weekly, November 27, pp. M138-48.

- Uchikawa, Shuji (1998), Indian Textile Industry: State Policy, Liberalization and Growth, Delhi, Manohar.

- Vijayabaskar, M (2011), “Global Crises, Welfare Provision and Coping Strategies of Labour in Trippur”, Economic and Political Weekly, Vol. 46, No.22.

- Vijayabaskar, M and J. Jeyarabjan (2011), The Institutional Milieu of Skill Formation: A Comparative Study of Two Textile Regions in India and China, in Moriki Ohara, M. Vijayabaskar and Hong Lin (ed.), Industrial Dynamics in China and India: Firms, Clusters, and Different Growth Paths, Hampshire, Palgrave Macmillan.