Donna Franklin

School of Communications and Contemporary Arts, Edith Cowan University

Gary Cass

Faculty of Natural and Agricultural Science, the University of Western Australia

([email protected])

Imagine a fabric that grows…a garment that forms itself without a single stitch!

The Micro‘be’ project investigates the practical and cultural biosynthesis of microbiology – to explore forms of futuristic dress-making and textile technologies. Instead of lifeless weaving machines producing the textile, living microbes will ferment a garment. It smells like red wine and feels like sludge when wet, but the cotton-like cellulose dress fits snugly as a second skin. The material is very delicate, comprising micro-fibrils of cellulose. The colouration of the fabric will depend on the wine used, red wine – red fabric, white wine or beer – a translucent material. A fermented garment will not only rupture the meaning of traditional interactions with body and clothing; but will also examine the practicalities and cultural implications of commercialisation. This project redefines the production of woven materials. By combining art and science knowledge and with a little inventiveness, the ultimate goal will be to produce a bacterial fermented seamless garment that forms without a single stitch.

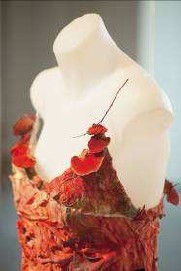

‘Fibre Reactive’, fashioned from the mycelium and fruiting bodies of the fungus, Pycnoporus coccineus (orange bracket fungus) was exhibited at the Biennale of Electronic Art Perth (BEAP), 2004. Photo: Robert Frith.

Imagine a fabric that grows…a garment that forms itself without a single stitch! The Micro’be’ project is attempting to do just this. The project aims to develop innovative research into the production of unique fermented garments grown from a novel method of using bacteria that creates cellulose. The Micro‘be’ team will investigate the practical and cultural biosynthesis of microbiology – to explore forms of futuristic dress-making and textile technologies. Instead of lifeless weaving machines producing the textile, living microbes will ferment a garment. A fermented garment will not only rupture the meaning of traditional interactions with body and clothing; but will also examine the practicalities and cultural implications of commercialisation. This project redefines the production of woven materials.

Franklin a contemporary textile artist and Cass a scientific technician combined their forms of knowledge and with a little inventiveness; a new system will result in the bacteria’s fermentation of a garment. This new collaborative project Micro‘be’ fermented wear, allows the biological clothes to be worn on the body without issues of fragility or outside contamination. This collaboration was also made possible by the unique environment of SymbioticA: The Art and Science Collaborative Research Laboratory at the University of Western Australia (www.symbiotica. uwa.edu.au). SymbioticA is in an exceptional position to link university faculties by integrating science and the arts.

New technologies are rapidly shaping our understanding of reality, identity and environment. It is therefore important for the arts to evaluate these potential futures, as they will inevitably impact upon sociological and cultural awareness. The development of biotechnologies takes technological integration beyond the mere mechanical to a real visceral level. With these new biological textile techniques, the Micro’be’ project will prepare the garments to be documented and taken out of the laboratory and into the public sphere. This will then act as a catalyst for debate and an invitation to engage/be confronted with the biotechnologically fermented clothes and the cultural issues this raises. The Micro’be’ garment will not only rupture the meaning of traditional interactions with body and clothing; but also raise questions around the contentious nature of bacterial biotech processes themselves.

One of the fermented Micro’be’ garments. Red material around the sides of the top and skirt is cultured from red wine. The Amber-opaque material insert is cultured from beer.

The Micro’be’ material at this early stage of development smells like red wine and feels like sludge when wet, but the cotton-like cellulose dress fits snugly as a second skin. It is very delicate, comprising micro-fibrils of cellulose. The unique bacterial fermented dress, made from wine, could mark the start of fabrics fermented by living microbes entering the $330 million per annum Australian textile manufacturing industry. Inspiration for the cellulose garments came when Cass noticed a skin-like layer covering a vat of wine that had been contaminated with bacteria and gone ‘off’. The bacteria that caused the spoilage were a colony of Acetobacter, transforming the wine into vinegar. The by-product of this activity is the formation of cellulose, a slimy, rubbery, soft, skin like substance. This substance termed the ‘vinegar mother’ originates from the ancient European; a few millenniums ago they believed that it was the skin of mother that ‘gives birth’ to the vinegar once it was placed in the wine.

Non-hazardous and non-pathogenic bacteria, Acetobacter are rod shaped bacteria, 1-4µm in size. They are aerobic (requiring oxygen) and can be found to be motile or non-motile. Acetobacter are distinguished by their ability to convert ethanol (wine) to acetic acid (vinegar). Another feature of Acetobacter is the synthesis of large quantities of micro fibrils of pure cellulose. An explanation for the synthesis of this cellulose is to keep the bacteria close to the surface. The organic Micro‘be’ fabric is biodegradable benefiting the textile community and environment by developing new ways to approach textile manufacturing. These organic textiles produce their own colour and structure, providing an eco-friendly “conceptual” alternative to cloth manufacturing – drawing attention to environmental conservation.

The fashion industry is always looking for something new and novel and has to deal with a labour intensive process which has been abused in the past with issues such as child labour. With growing use of synthetic materials and genetically modified products in an increasingly environmentally conscious world, the Micro’be’ project’s material is the ultimate in environmentally friendly textiles. As the material produced by the action of a bacterial culture on the alcohol is cellulose, it is naturally degradable in the environment. The Micro’be’ material has the future potential to compete against other textiles by offering a low production cost material for fashion that is adaptable and has the potential to replace synthetic materials in manufacture. Due to the rising global oil price, the cost of synthetic materials is becoming increasingly expensive. This product will allow for a greater choice of organic/low impact materials for the fashion industry. As the fabric is naturally grown it minimises the use of machinery it offers a ‘green’ alternative to traditional carbon producing textiles manufacture. This may appeal to an increasingly ‘green’ oriented consumer market. The colouration of the fabric can be varied based on the alcohol used in manufacture. For example, red wine gives red fabric and white wine or beer creates a translucent, see through material (Fig shown above).

The most important advantage over conventional textiles that the Micro’be’ material has is the potential for manufacturers to save on the high labour costs of patterning, cutting and stitching the final garment. As such, it has the potential to reinvigorate the Australian textile manufacturing industry and effectively compete against low-labour cost countries who currently dominate the global textile industry. This project also develops Australia’s reputation for innovation in environmental and bio-degradable technologies. One major problem with the Micro’be’ fermented fabric is that it lacks flexibility, which in turn reduces wearability. We aim to rectify this issue soon, producing a garment that will be suitable for commercial use. Several chemical trials have achieved some success, giving an optimistic future for solving the flexibility drawback. Also the material has a distinctive smell, smelling like a hangover or a kind of morning-after-the-night-before smell; a kind of stale alcohol aroma. It is strongly believed that this later problem will be resolved with the chemical treatments used to fix the flexibility issue.

Once the initial teething problems of the material are overcome, this material will be a cost effective, low environmental impact, labour friendly and biodegradable textile donned by the world as a fermented garment. An important objective of the textile and sports industry is the production of seamless wear. One of the future aims of the Micro’be’ project is to produce seamless garments. By using the bacteria to form the garment, we can replace weaving machinery that presently is not capable of producing 3-D seamless wear. Small scale tests with the Micro’be’ project have successfully produced a seamless item of clothing. This too, needs further research to perfect the technique and scaling up in size.

The ultimate goal of the Micro’be’ project will be to create a seamless, biosynthetic garment that forms without a single stitch.